Pentecost 10 – 2024

John 6:1-21

Marian Free

In the name of God who delights in the ordinary and who feeds us – body, mind and soul. Amen.

Sometimes I wonder if we take ourselves (and therefore our faith) too seriously. Jesus’ feeding of the 5,000 is one such example. Much ink has been spilled in the attempt to explain just what happened. Was it a miracle in the sense that Jesus was able to turn five small loaves into enough bread to feed such an enormous crowd? OR was the miracle the small boy’s offering – which in turn exposed the selfishness of the crowd who then produced the food that they had brought with them? If wondering about the miracle were not enough, others (like myself last week) focus on what the author’s intention was in re-telling the story. For example, as I said, Mark seems to be deliberately contrasting Jesus’ selflessness and humility with Herod’s self-centredness and pride. John, as we shall see, uses the miracle as a stepping off point for a long discourse on bread and possibly on Eucharistic theology.

Knowing the scholarship adds depth and breadth to our understanding, but it doesn’t hurt to have a more playful look at the text, to wonder at the detail and to try to put ourselves into the story. Instead of asking about meaning, we can take the story at face value and imagine it being related to a congregation of believers who might be trying to get a sense of what it was like to be in the presence of Jesus. Sometimes little details stand out and bring a smile to our face reminding us that Jesus was real, that he was human just like us, that the disciples didn’t completely understand or trust Jesus (a bit like us) that the people who followed Jesus were interested in him because of what he could do (at least a little bit like us).

So, Jesus – who if we read back – has just finished a long dispute with the Jewish authorities randomly decides to go to the other side of the Sea of Galilee. We are not told how he gets there! A large crowd continues to follow him either because they are interested in his showmanship or because they believe he has the power to heal. When Jesus gets to the other side of the Sea, he goes up the mountain and sits down with his disciples – only then does he appear to notice the crowd coming up behind.

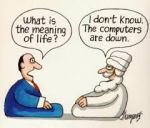

He doesn’t teach (as in Mark and Luke) or heal (as in Matthew and Luke) but turns to Philip and poses a “teaser[1]”: “Where are we to buy enough bread for these people to eat?” We can imagine Jesus’ lips curling slightly and his eyes twinkling as he tries to suppress a smile. He knows ahead of time that Philip will take him seriously and misunderstand him. Perhaps Jesus even imagines Philip doing the maths in his head. Indeed, Philip doesn’t even answer Jesus’ question which was “where” not “how” will we buy bread.

Then “miraculously’ the bread appears in the form of a small boy who has brought his lunch to Andrew and in Andrew who, even though he thinks the offering much too small, still brings the boy to Jesus. Jesus makes no comment about the bread but tells Andrew to make the peoples sit down and, as if it is an important detail, the gospel writer tells us that there was a “great deal of grass in the place”. (Mark and Matthew mention the grass, or the green grass, but not how much there is.) This comment about the grass, adds nothing to the miracle story, but it does situate the story and allows us to picture the scene and to put ourselves in it.

I draw out these details rather than the number fed, or the baskets left over, to demonstrate the ways in which the author has tried to make the text come alive for his listeners. Through this retelling, we are shown Jesus’ initial indifference (not that he doesn’t care, but that he is so focussed on what he is doing that he doesn’t at first notice the crowd). We can also see something of Jesus’ playfulness – life doesn’t have to be taken too seriously! At the same time through Philip, we can see the consequences of taking things too seriously – we get the wrong end of the stick, we look for the wrong solution, we don’t listen carefully to the question! In Andrew, we observe the faith that is tentative, but not afraid of being disparaged or put down. Lastly, the plentiful grass is evidence that however we understand it, and however it actually happened, there was a time and a place when a great crowd gathered around Jesus, sat on the grass, and were fed.

If we pay attention to the detail, it is easier to see what is going on, and to put ourselves into the picture – are we part of the crowd, or do we relate to the pragmatic Philip or to the hesitant Andrew? How do we feel about Jesus’ gentle teasing of Philip? What do we make of the “great deal of grass”?

The Ignatians have a method of reading the bible which might be called imaginative contemplation. This method invites us to approach the bible with all our senses, to see, hear, feel and smell what is happening, to put ourselves into the story as one of the characters and to imagine what they are thinking[2]. To do this, you first open oneself to the presence of God, before reading the passage slowly once or twice so as to become familiar with it. Then you try to put yourself in the story as one of the people or simply as an observer (perhaps a maid from the inn peaking in on the Nativity). Finally, you turn to Jesus and speak to him. If you’d like to try. This method, John 6:1-21 would be a good place to start.

Who knows what really happened and what the miracle of the feeding really was, but from this story we learn that Jesus was real, that he had a sense of humour and that he cared, about the whole person – body, mind and soul, and that the people needed full stomachs as much as they needed to hear him or to be cured of their illnesses.

[1] A much better word than ‘test”.

[2] Christina Miller gives a simple explanation here https://blog.bible/bible-engagers-blog/entry/ignatian-contemplation-how-to-read-the-bible-with-your-imagination