Christmas Eve – 2025

Luke 2:1-14

Marian Free

In the name of God who reveals Godself to the most unlikely, the most uneducated and most despised and who entrusts them with the message of salvation. Amen.

There are so many sub-plots to the Christmas narrative that it is impossible to do justice to all the different elements.

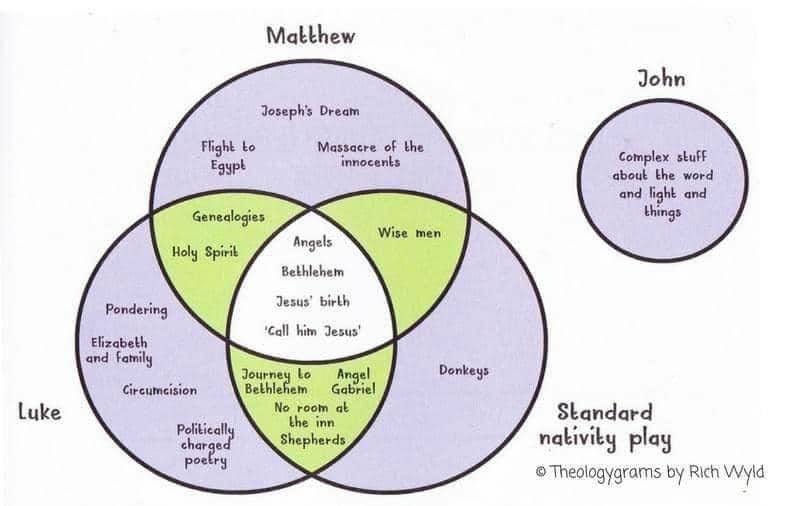

So where does one start to explore the Christmas narrative – with the announcement of Jesus’ birth to Mary or to Joseph, the journey to Bethlehem, the inn keeper who found room, the shepherds, the angels, the magi, the star? We could as some do, let our imaginations go wild and wonder about the reactions of the donkey who carried Mary or animals in the barn where Jesus was born, or we could invent characters like the little drummer boy (What makes anyone think that a sleep deprived mother would be grateful when a young, uninvited guest strikes up a drumbeat in her crowded accommodation?)

This year, I found myself thinking about the shepherds, their place in the story and what they have to tell us.

It is easy to be sentimental about the shepherds, who in our nativity scenes are respectable, if poor men out in the fields protecting their sheep, shepherds who are suddenly surprised by not one but a whole host of angels; shepherds who leave everything to race to Bethlehem with white fluffy lambs in the crook of their arms and shepherds whose role is to bear witness to Jesus’ birth.

But when we ignore the picture-perfect Christmas cards and pay close attention, we discover that there is much more to the story of the shepherds. The shepherds, whom we are led to believe are and humble, decent men were, in reality, among the most despised people in Jesus’ day. In the ancient Middle East shepherds were usually itinerant workers, moving from place to place in search of work, and taking whatever work they could find.

Shepherding was not a job of choice. A shepherd was always on the move looking for pasture and a shepherd had to be on guard day and night to protect the sheep from bears, lions, foxes and other threats which might just as well kill a shepherd as a sheep. Shepherds were living and sleeping rough without proper protection from the elements and who were reputed to be thieves, suspected of stealing the sheep they were supposed to protect. A few, if not all, would take comfort in the bottle to keep them warm at night.

In short, if you were to draw up a list of people who were worthy to be the first to receive notice of Jesus’ birth, the shepherds would not even make the long list. And yet here they are so they must have something to teach us. When we look at the story with the shepherds in mind we notice a number of things.

First of all, after they overcome their terror, the shepherds believe the message of the angels and respond immediately. There is no hint that they think the angel’s story is too ridiculous to be true. The angel has said that the Saviour, the Christ has been born and so it must be. And, even though the only clue to the baby’s whereabouts is that, like every other baby in Bethlehem, the child will be wrapped in swaddling cloths in a manger, the shepherds leave everything, including their sheep and hurry to Bethlehem to see the child for themselves.

Second, even though the shepherds were usually shunned and ignored, they could not stop themselves from sharing the good news with everyone. This means that, the shepherds, the marginalised and despised, become the first evangelists – the first to share the good news.

Third, the shepherds were so overwhelmed with what they heard and saw that they couldn’t stop praising and glorifying God.

Fourth, the shepherds did not give a moment’s thought as to what might happen to the sheep when they abandoned them to go to Bethlehem – that is they did not look behind them but trusted the sheep to God.

Last, and this is probably Luke’s point, by sending angels to the shepherds, we are shown that God often chooses the least respected, the least equipped, and the least expected to be the first to hear the good news, and that God’s faith in the shepherds was proved right when the excitement and passion of the shepherds gave them credibility which ensured that their message was heard.

It is always tempting for us to believe that the task of evangelism belongs to those who are more articulate, more authoritative, and more attractive than we are. But if God can choose and use those disreputable scoundrels – the shepherds – God can and will choose and use us. And when God does reveal godself to us, the response of the shepherds can be a model for our own reaction.

The shepherds are open and receptive to the unexpected presence of the angels, they are not suspicious, but respond immediately to the angel’s news with joy and enthusiasm. They trust God that what they leave behind will come to no harm. They find the experience of coming face-to-face with God’s messengers so overwhelming that they simply cannot keep the news to themselves and they respond to all that has happened by praising God.

For us tonight, the story of Christ’s birth lacks the novelty of that first Christmas, but that does not mean that we should not be open and receptive to the possibility of God’s revealing godself to us in the here. and now. Let us pray that when that happens and however that happens, we like the shepherds will be sufficiently open to the possibility that God that we will take heed and respond immediately. Is the good news that brings us here tonight so extraordinary that we. cannot keep it to ourselves? Can we trust God enough to leave the past behind and step into an uncertain future? Do we really believe that God can and will use us to share the story of God’s presence in the world – shepherds and kings, poor and rich, homeless and housed, ignorant and educated?

If we do surely that is certainly cause for praising and glorifying God.