Christmas – 2022

Marian Free

In the name of God who comes among us silently, unobtrusively and unremarkably. Amen.

In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. . . . All things came to be through him, and without him nothing came to be. —John 1:1, 3

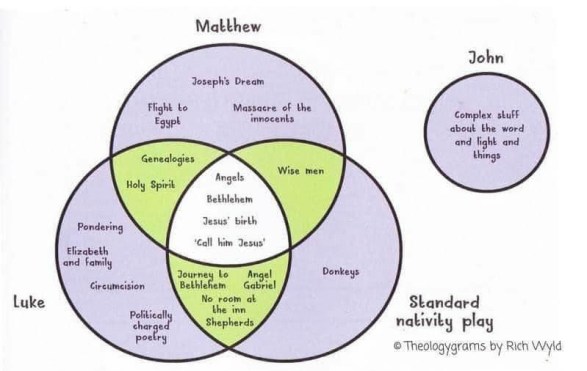

During the week our Bishop posted the above photo in Facebook. It is a light-hearted attempt to compare the accounts of Jesus’ birth in the four gospels. At the same time, it reminds us that when it comes to Christmas, we conflate two versions of the story – our nativity scenes. have the shepherds and the magi even though the shepherds are found only in Luke and the magi only in Matthew. (Mark is missing, because in Mark’s gospel, Jesus bursts on to the scene fully grown.) When the post appeared, discerning viewers noticed at once that Mary was not included in the diagramme. You might like to compare the first few chapters of Luke and Matthew and see if anything else needs to be added. The four gospels begin quite differently and as might be expected, the beginnings reflect the interests of the authors. Matthew is concerned to stress the Jewishness of Jesus and the way in which his early years demonstrate the fulfillment of Old Testament promises. (“This was to fulfill what was spoken by the prophets” occurs 5 times in the birth narrative.) What is more Matthew’s genealogy goes back to Abraham – the founder of the Jewish faith. Luke, on the other hand is more concerned with the universal implications of Jesus’ birth and with the historical context in which the story takes place. Luke includes the census and mentions Herod. His genealogy goes all the way back to Adam – indicating that Jesus is for everyone, not just for a few. Mark, as I said is not concerned with Jesus’ origins and John’s poetic start gives us – not a birth, but a cosmic beginning. From John’s point of view Jesus always was.

Does it matter that we do not have a consistent account to explain Jesus’ presence among us? Do we need to explain the differences? Of course not. Each story tells us something different, helps to satisfy our curiosity about Jesus’ beginnings and enriches our understanding of something that is essentially beyond our understanding. Indeed, Richard Rohr would argue that Jesus’ birth is only one expression of God’s incarnation among us – the account/s of Jesus’ birth are only one expression of God’s presence among us. That is to say, prior to Jesus’ birth, God was not absent in creation, invisible to God’s people or inactive in relation to the world. From the moment God said: “Let there be light” God has been dynamically engaged with creation and constantly in relationship with God’s people.

As Rohr says, we will never know the how, why or when of creation, but most traditions suggest that everything that it is the creation of some “Primal Source, which originally existed only as Spirit.” He goes on to say that “This Infinite Primal Source somehow poured itself into finite, visible forms, creating everything from rocks to water, plants, organisms, animals, and human beings. This self-disclosure of whomever you call God into physical creation was the first Incarnation (the general term for any enfleshment of spirit), long before the personal, second Incarnation that Christians believe happened with Jesus.”

What this means is that from the beginning of creation God has existed/been incarnate within all creation – animate and inanimate. When God ‘became flesh’ in the person of Jesus, God became incarnate in a very particular way – uniting Godself to us. At that point in time, God the creator, with the Logos/Word, fully identified with humankind, proving once and for all, that humanity is created in the image of God and that God is incarnate in and with us – not simply in creation or in some indistinct, immaterial form out of sight and out of reach. God, through God’s incarnation in Jesus that God chooses not only to be incarnate in the beauty of a sunset, the perfection of a flower, the majesty of a mountain, but in the frailty of human flesh, the imperfection of human behaviour, and the weakness of human will. Thanks to God’s coming in flesh – in Jesus – we can see God in one another and in ourselves and, in Jesus, we can see too what it is that we can be.

So, this year, let us not look back with longing to the infant in the stable or forward with anticipation to the coming of the Son of Man, but let us simply look – around and within – so that we might perceive God’s incarnation in its many and myriad forms – in the world and in ourselves. Let us celebrate God, with us throughout all time.