Lent 4 – 2015

John 3:14-21

Marian Free

God of contradiction, open our hearts and minds to understand that your ways are not our ways and your thoughts are not our thoughts. Amen.

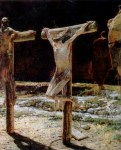

The crucifixion of Jesus has been portrayed in a wide variety of ways from the pious and sentimental to the violent and grotesque. Many are confronting (if for different reasons). For example I feel some disquiet when I see an image of Jesus fully dressed (in Bishop’s regalia) and exhibiting no signs of pain. Equally confronting is one from South America that depicts what looks like a charred body arched in pain and screaming in agony. For centuries the crucified Jesus was depicted as white (often blond). During the twentieth century new and original images emerged that more accurately reflected Jesus as a representative of all humanity – or example a Jesus with Chinese, Maori or African features. Sidney Nolan portrayed Jesus as a woman as did the artist whose sculpture was placed in a United Church in Toronto. Such imagery enables women and those whose skin colour is not white to fully grasp the notion that Jesus died for all people – including them – and not just for white (middle class) males.

New and confronting images of the crucifixion can help to make real the horror of the crucifixion. They can enable us to peel back the layers of piety that have, over the centuries, stripped the cross of its meaning. Our churches have crosses in all kinds of shapes and designs. There are wooden crosses, brass crosses, crosses made of silver or gold and crosses that are encrusted with jewels. Crosses in a number of different designs are worn as jewellery – even by those who do not profess the Christian faith. In many cases, the image of cross even when it is adorned with a crucified Christ has become so familiar that it has lost its power to confront and to challenge.

That said, I’m not at all sure that we would wish to be confronted with the horror of the crucifixion on a daily basis. We are told that crucifixion was an awful way in which to die. Whether a person was nailed or tied to a cross, they died slowly and of suffocation – pushing down on their nailed (or bound) feet so that they could take a breath[1]. It could take as long as three days to die. Crucifixion was also a very public death. Those who were condemned to die were generally put to death by the side of a well-travelled road so that their deaths could serve as an example to as many people as possible. It was a cruel, inhumane and humiliating way in which to die and, one would think, the most unlikely image to become an object of veneration.

This contradiction – that an image of torture and death could become a symbol representative of life and hope – is captured by the author of John’s gospel. In 3:14-15 Jesus says: “the Son of Man must be lifted up so that whomever believes in him will have eternal life.” In this passage and other places in which Jesus uses the expression “lifted up”, he is referring to his crucifixion. (“And I, when I am lifted up from the earth will draw all people to myself.” (12:32)) For the author of John’s gospel the cross, the crucifixion is the high point of Jesus’ ministry, the moment towards which the whole gospel is moving and the point at which it Jesus’ mission reaches not only its climax, but its fulfillment. The cross is a victory, not a defeat.

Lindars points out that Jesus’ victory on the cross is at least two-fold[2]. By laying dow his life for others, Jesus is demonstrating not only his deep love, but what is really God’s love for the world. In freely offering this gift, Jesus shows his readiness to do as the Father wills and demonstrates that he and the Father are one. Lindars refers to this as his “moral union with God”.

By overcoming the natural human resistance to pain and death and by conquering the human will to live, Jesus shows that human nature’s propensity to resist God and goodness can in fact be overcome and that humanity does not have to submit to selfish desires or to the propensity to gratify one’s own needs and desires before all else. Through his submission to the cross Jesus, Lindars suggests, wins the “supreme moral victory” (which is also a cosmic victory for “in his own person the devil’s grip on humanity is broken” (12:31)).

“Lifting up” in John’s gospel several layers of meaning. It can refer to the cross as the place of victory but it also suggestive of Jesus’ exaltation to the right hand of the Father. At the same time, because as we have seen, crucifixion was a very public event and because the cross lifted the victim above the level of the crowds the condemned men were very visible to those who gathered and to those who passed by. On the cross, Jesus is visibly and publicly displayed for all to see. Thank goodness we do not have to witness the physical event, but through the images that are available and those in our mind’s eye, we see Jesus’ lifted up and through John’s gospel comprehend that in this instance defeat is in fact victory, that death is a door to life and that even the worst of human excesses can be overcome.

We come to understand that on the cross, Jesus bore all the suffering of the world, experienced the baseness and cruelty of humankind at its worst and identified with the victims of cruelty and torture, the victims of domestic violence and bullying, the victims of oppression and injustice and all who have suffered at the hands of others. Those who have experienced unbearable pain and suffering can look at the cross and know that God shared/shares their pain. This understanding is best captured by a poem written by a woman who had experienced abuse at the hands of a man. The poem is written in response to a cruciform image of a woman that was hung below a cross in a United Church Chapel in Toronto.

May we all see in Jesus “lifted up” the victory of the cross, Jesus union with the Father, the triumph over evil and the possibility of resurrection.

By his wounds you have been healed

1 Peter 2:24

O God,

through the image of a woman

crucified on the cross

I understand at last.

For over hold my life

I have been ashamed

of the scars I bear.

These scars tell an ugly story,

a common story,

about a girl who is the victim

when a man acts out his fantasies.

In the warmth, peace and sunlight of your presence

I was able to uncurl my tightly clenched fists.

for the first time

I felt your suffering presence with me

in that event.

I have known you as a vulnerable baby,

as a brother and as a father.

Now I know you as a woman.

You we’re there with me as the violated girl

caught in helpless suffering.

The chains of shame and fear

no longer bind my heart and body.

A slow fire of compassion and forgiveness

is kindled.

my tears fall now

for man as well as woman.

You, God,

can make our violated bodies

vessels of love and comfort

to such a desperate man.

I am honored

to carry this womanly power

within my body and soul.

You were not ashamed of your wounds.

You showed them to Thomas

as marks of your ordeal and death.

I will no longer hide these wounds of mine.

I will bear them gracefully.

They tell a resurrection story.

Anonymous. Written after seeing a figure of a woman, arms outstretched as if crucified, hung below the cross in the Chapel of the Bloor St United Church in Toronto. The statue is now in a courtyard of Emmanuel United College in Toronto.[3]

[1] A Google search of images of the crucifixion provides some sketches which demonstrate what crucifixion was like.

[2] Lindars, Barnabas, SSF in The Johannine Literature. Ed Lindars, Barnabas, Edwards, Ruth B. and Court, John. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 2000, 91-93.

[3] The poem is anonymous. I read it in a Newsletter published by The World Council of Churches in 1988 as a part of the Ecumenical Decade of Churches in Solidarity with Women (1988-1998).