Pentecost 14 – 2023

Matthew 16:21-28

Marian Free

In the name of God who sees us as we are and does not turn God’s back on us. Amen.

“Zora’s home, or at least the part that can still be lived in, has shrunk to a third of its original size. The bedrooms have long been abandoned to the wind and the snow, which gets in through the tears in the bin bags, while the bathroom, devoid of water and reeking of blocked drains, is also avoided. The doors to these rooms are kept shut, rolled-up rugs wedged against them to keep out the icy draughts from one side and the stench from the other. Consequently, the narrow entrance hall is now not so much a corridor as a tunnel, which, bristling with Zora’s works of rubble, shrapnel and feathers, channels guest directly from the front door to the living room at the far end of the flat. The kitchen, the favoured room in the spring and the summer, as it is the furthest room from the hills and so least likely to be shelled, has now lost its former status due to the cold. Ice spiders crawl over the inside of the windowpane and icicles hang from the windowsill. Mirsad helps Zora drag the mattress from the kitchen to the living room so that she can sleep near the stove. The kitchen is now used mainly as a place to relieve herself, using a bucket as a chamber pot. Zora disposes of the bucket’s contents outside the building, close to the mounds of uncollected rubbish, on her way to find food or water each morning. The area immediately around the stove, where the mattress, stools and cushions have been arranged, has become the hub of the flat. Almost all activity takes place there: cooking, sitting, eating, talking, making art, washing with a glassful of icy water and a bucket, and sleeping. [..] The flat is drawing in on itself, Zora thinks as she inches closer to the stove each night. It’s being taken over, room by room, by ice, wind and snow. By the outside by the war.”

I have just completed the novel Black Butterflies by Priscilla Morris about the siege of Sarajevo. Morris describes in graphic detail what it was to live under siege in bombed out homes, as the European winter closed in and UN food drops were prevented from entering the city.

It is extraordinary to imagine that friends and neighbors could turn against each other so quickly. That they could allow others to endure incredible deprivation seems unbelievable and yet the situation described above is one that many in the Ukraine will face as the war there enters its second winter – a war in which infrastructure including power stations has been destroyed, and food storages destroyed.

I name the Ukraine only because the situation is similar to Sarajevo in many ways, particularly in relation to the cold, but there are countless other situations in which people endure the horrors of war, the anguish of famine, the indignity of being a refugee or asylum seeker, or the long, hard struggle to recover from natural disaster.

As members of the human race, you and I have to face up to the unspeakable horrors we inflict/have inflicted on our fellow human beings, the tragedies on which we turn our backs and the times when we offer too little or inappropriate assistance.

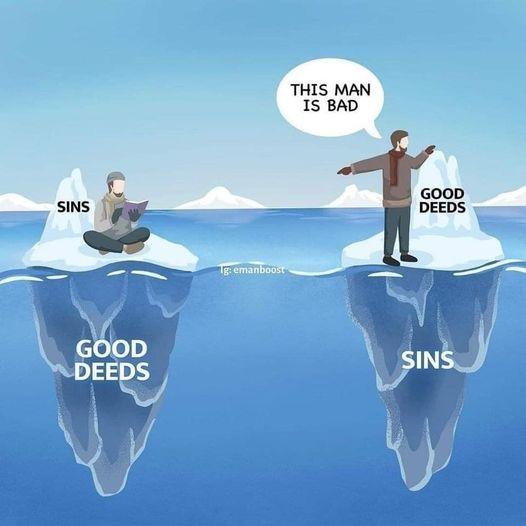

Over the last few weeks, the readings in Morning Prayer have followed the life of King David. As I have read this account one more time, I have had cause to reflect that the Bible has as much (if not more) to say about humanity as it has to say about God. In other words, the Bible holds up a mirror to reveal the worst, as well as the best in us. The Old Testament in particular shows us of what we are capable – murder, adultery, genocide, fratricide, self-centredness, jealousy, craftiness, and deception to name but a few. Our Old Testament heroes are depicted as vengeful, cowardly, covetous, two-faced, and faithless. (Though they can also be brave, faithful, selfless, humble, and repentant ).

In the New Testament our heroes fare only a little better. In the time of Jesus Israel and the neighboring countries are under Roman rule and therefore not at war with each other and there is no throne for which the descendants of David can compete. This means that the flaws of the disciples are therefore of a different order, but their raw humanity is fully on display and they exhibit imperfections shared by us all. They are foolish, fearful, competitive, uncomprehending, disloyal, cowardly, impotent, and self-seeking and there is no attempt by the gospel writers to present them as anything other than what they are.

Today’s gospel is a dramatic illustration of just how uncomprehending and self-important the disciples are. As we heard last Sunday, the disciples have just been entrusted with the true identity of Jesus – “you are the Christ, the son of the Living God.” That they have no idea what this means is revealed by their reaction to Jesus’ announcement that he will suffer and die. On this first occasion Peter goes so far as to rebuke Jesus. (Earning Jesus’ swift and harsh reaction: “Get behind me Satan!” ).

On the next two occasions that Jesus’ announces his future suffering, the disciples’ response exposes not just their incomprehension, but also their arrogance and competitiveness. (Jesus shares with them his deepest fears and they can only think of themselves! ) They argue about who among them is the greatest and the mother of James and John asks Jesus if they can sit at his right hand and his left in the kingdom! Finally, when Jesus’ predictions do come true the disciples abandon him to suffer alone. Fearful of reprisals they hide away until they are truly convinced that Jesus has risen. They can hardly be said to be role models for those who follow after, but what they are is authentic, flawed and blatantly human.

As much as the Bible helps us to understand God, it gives us an insight into ourselves, and forces us to be honest about our weaknesses and vulnerabilities. It takes away any tendency to self-importance and, time and again, throws us on the mercy of God. What is extraordinary, and what is made clear. in the very imperfect lives of our forebears in faith, is that through it all, God never turns God’s back on us, but reaches out to us, over and over and over again, hoping against hope that we will learn to trust God more than we trust ourselves and that, empowered by God, we will become the people that we are destined to become.