Pentecost 16 – 2025

Luke 16:19-31

Marian Free

In the name of God whose preference is for the poor, the widowed and the orphaned. Amen.

During the week I learnt a new expression which was coined to describe Elizabeth Gilbert’s book Eat, Pray, Love[1]. The expression “Priv Lit” or “Privileged Literature” was introduced in 2010 by writers Joshunda Sanders and Diana Barnes-Brown in an article titled Eat, Pray, Spend. I came across the expression in a comment on Gilbert’s latest offering All the Way to the River in which (as I understand it) Gilbert describes the wild ride she and her lover go on when the latter is diagnosed with cancer. The expression ‘Priv Lit’ refers to: “literature or media whose expressed goal is one of spiritual, existential, or philosophical enlightenment contingent upon women’s hard work, commitment, and patience, but whose actual barriers to entry are primarily financial”.

Authors of these sorts of biographical narratives use their own life experiences as a model for others, assuming that these can be universalised and forgetting that they write from a position of wealth and privilege that few others can aspire to.

While this term was first applied to Gilbert, it could just as well refer to a number of other authors who are so focussed on their own issues (and resulting solutions) that they are blind to the very real problems faced by women (children and men) all over the world – including in their own country of the United States. Self-actualisation, dealing with grief through travel, or restoring a villa in Italy pale into insignificance in comparison with the hour-by-hour struggles of homelessness, starvation, injury and loss experienced right now by millions in Gaza, the Sudan and elsewhere. These (usually expensive) “solutions” to pain and grief are meaningless to the millions struggling to survive in many of first world countries who cannot afford homes or, who if they have homes have to decide between keeping the lights on and feeding their children.

In today’s parable the unnamed rich man could (like the authors above) be described as tone-deaf and blind. Lazarus, the only person named in parable, lies at the gate of the rich man. It is inconceivable that the rich man doesn’t know that he is there, or that Lazarus is hungry, dependent and covered in sores that are licked by dogs. Not only would the rich man have to pass Lazarus every time he left the house, but Lazarus would also have been visible from within the house. The architecture of the time was such that even the homes of the wealthy were built directly on the street, and those going past would have been able to see inside to the courtyard. Lazarus would have been able to at least glimpse the goings-on inside the home and maybe the obvious signs of wealth. All the daily to-ing and fro-ing, including the delivery of food, would have to have passed by him[2].

There was nothing in the way of social services in the first century Mediterranean. Those without families, those unable to work, the widowed and orphaned were often forced to beg. Jewish law made up for this lack by building into it an obligation to provide for the poor, the widowed and the orphaned not, as AI helpfully summarises, “as an optional act of charity, but as a fundamental expression of the righteousness and justice of God”. This is perhaps most clearly expressed in Deuteronomy 15:7, 11 – “If there is among you anyone in need, a member of your community in any of your towns within the land that the LORD your God is giving you, do not be hard-hearted or tight-fisted toward your needy neighbour.” “Since there will never cease to be some in need on the earth, I therefore command you, ‘Open your hand to the poor and needy neighbour in your land.’”[3]

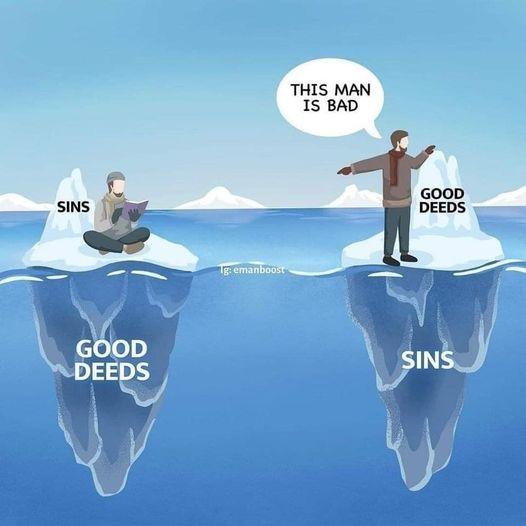

The rich man in the parable was a Jew; he knew the law; as we learn when he appeals to Father Abraham after his death. In life though, the rich man appears to have no self-awareness, no understanding that his wealth is a privilege not a right, and no concept of the obligations his position and his faith entails. He is either so self-absorbed, or so self-righteous or perhaps so disgusted by Lazarus’ condition that he looks right past or right through him.

We live in a time in which the problems facing the world seem insurmountable. Many of us find ourselves frozen in indecision because any contribution we can make to the solution is but a drop in the ocean. On our own we cannot impact the systemic abuses that lead to entrenched poverty, we cannot end the wars in the Ukraine, in Gaza, in the Sudan and elsewhere, and we can’t, as individuals, stop climate change. We can, however, examine our own lives and try to understand how our attitudes, our lifestyles and even our political allegiances impact the poorest of the poor. We can try to understand how systems we unwittingly support further entrench poverty and inequity. We can recognise and be thankful for the advantages that we do have and acknowledge that throughout the world and in our own nation there are those who, through no fault of their own live in situations of dire poverty, unable to properly house and feed themselves or their families let alone manage to fund health.

If nothing else this parable urges us not turn away, but to keep our eyes firmly focussed on the state of the world around us, to try to comprehend (and change) the systems that trap people in poverty and to do all in our power to ensure that all people have adequate access to food and shelter, health care and education.

Like the rich man (and his brothers) we already know what to do – it is all there in our scriptures.

He has told you, O mortal, what is good;

and what does the LORD require of you

but to do justice, and to love kindness,

and to walk humbly with your God? (Micah 6:8)

Today is the day to open our eyes and ears to the cries of the poor, the oppressed and the overlooked.

This poem could be our daily prayer:

If it should be, loving Father of all,

that, all unknown to us,

our eating causes others to starve,

our plenty springs from other’s poverty,

or our choice feeds off other’s denial,

then, Lord,

forgive us,

enlighten us,

and strengthen us to work for fairer trade

and just reward. Amen. (Donald Hilton, Blessed be the Table)[4]

[1] Gilbert’s journey of self discovery was actually subsidized by her publisher.

[2] Many scholars assert that Luke was written for an audience that was well-off and urban dwelling. The inclusion of this parable, not found elsewhere, seems to support this view.

[3] Or this from Amos 6:4f Alas for those who lie on beds of ivory,

and lounge on their couches,

and eat lambs from the flock,

and calves from the stall;

who sing idle songs to the sound of the harp,

and like David improvise on instruments of music;

who drink wine from bowls,

and anoint themselves with the finest oils,

but are not grieved over the ruin of Joseph!

[4] Quoted by Chelsea Harmon, Working Preacher, September 25, 2022.